Ethics and the Beyond

Brad Samuels and Jay Aronsoninter·punct has a conversation with Brad Samuels of SITU - a unique tripartite architecture studio - and Jay Aronson, founder and director of the Center for Human Rights Science at Carnegie Mellon University. We speak about issues of emergent technologies, architectural agency, and the ethics with which we must all concern ourselves.

i•p:

What, from your perspective, is crucial to take away from an architectural education which allows one to work so dexterously between fields as you do at SITU?

Brad Samuels:

I think the idea of a class on interdisciplinarity is more of a red herring, not really the right way. Instead I think the curriculum itself and the nature of the questions being asked in studio need to be formulated as fundamentally reaching outside the disciplinary bounds of architecture. Then you can begin to understand your role outside the discipline, but also only after you have the foundation. You aren’t going to get around the NAAB requirements, you’ll still have to do all that stuff – but you can bring in advisors from outside to tackle architecture problem sets. The other part of that is leveraging, biasing, and putting weight on problem sets in other disciplines. Otherwise we risk becoming recursive architectural architecture for architects.

When we get out of school and have the opportunity to work, it’s a big shift from the experience in most schools. We’re not architects trying to impress architects with theories about buildings, rather we’re searching for ways to use the tools of architecture for means beyond just the building. Maybe it’s towards analytical ends, maybe it's a belief that buildings can heal – like MASSDesign Group. Either way, there are certainly limits to the agency of the architect, but we have to really look to find out where they are.

i•p: For both Brad and Jay: as architectural projects become ever more complex the role of the architect has profoundly shifted – to borrow some words; from master-builder to master-conductor. Particularly examining this situation with regard to social, activist, and research projects – what are your reflections on these entanglements and the role of the architect within them?

BS:

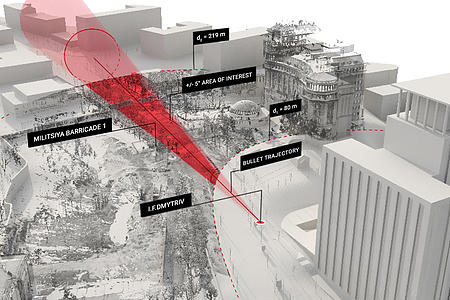

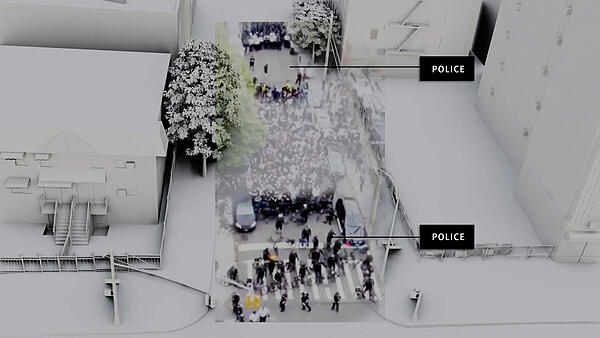

The unexpected role of the architect in research projects is really something. We have a particular set of tools, sophisticated ways of describing space, relevant analysis methodology, and yeah, maybe above all are skills in coordination. For example acoustic audio-latency analysis is beyond our competency, but we had conversations with ballistics experts about what could be done. The ability to have those conversations that are rigorous and spatial in many ways is architecture. I think in some ways you too, Jay, embody that master-coordinator role - so maybe you’re a defacto architect in that way.

Jay Aronson:

Maybe I’m not a master, but I do feel like a lot of my job is finding, or running into, people who have diverse and specific needs. Usually trying to make sense of a complicated situation in a complicated environment, and not really having the tools or the expertise to understand even what they want. We bring in people who not only can help achieve those goals, but more importantly help them understand what they need in the first place. In many ways if you have a client you can tell them this is the building you will get and I will perform it for you – or you can take the time to understand how they live their lives, what they want out of the space, and what services actually make sense for you to provide. It’s always a dance of what you want, as an architect or academic, and what your client wants. But the process of getting in sync about those goals is usually the most important part. Sometimes those kind of conversations don’t go anywhere - I spend a lot of time having what in the moment feels like a useless conversation, but over time builds up an understanding of what is productive and with whom, and allows me to judge what will be a good partnership or what won’t.

BS:

We should be advocating for useless conversations! The onus is always on productivity and outcomes, and as a pretense it always puts a tremendous burden on work which you don’t fully understand where it is going to go. The conferences you have put on have been defined for me by the lack of pressure to produce that outcome at the end. You curate a whole bunch of curious people who on paper have nothing to do with each other, but then you put them in a room together and it's kind of magic. Maybe we whiteboard at the end to recap, but there is no attempt to synthesize every possible outcome in that moment. Then in the weeks and months following these meetings the real conversations happen – that’s when the outcomes begin to become clear. I find it far more productive, in the genuine sense.

i·p:

This practice of gaining common ground feels deeply related to your respective work in Human Rights. How do you navigate the differences between enabling solutions and proposing them in such sensitive spaces?

JA:

For me, it’s an ethic. It’s an ethic of listening to what people need rather than telling them what they need. I often see it as a ‘traveling roadshow’ where mostly white, upper middle class, people travel around the world in a very comfortable existence staying in fancy hotels giving big talks and creating lofty goals. It’s totally disconnected from the realities on the ground.

This idea of solutionism where you try to market a fix without knowing what people’s problems really are. We first have to ask them, well what’s your problem? I might not have anything meaningful to say about it, or I might not be in a position to act on it - and if so, I’m going to be honest and tell you that. But if I do, then we can see if we can make something happen together. It’s important not to impose, or to mislead.

i•p:

When architects get involved that can certainly be a big issue. Do you worry about the conflicts of seductive images when attempting to present an-objective-as-possible reality?

BS:

That’s certainly a structural question. I wouldn’t argue that there is any kind of neutral representation, but the decision not to make a video and instead to create a platform you can move around and interrogate yourself is fundamental to its efficacy. You’re right that the idea that we’re layering a narrative on top of this is a huge liability in these contexts, so we try to present or allow for both. For example we have a super dense point cloud, and if you were to let the judges roam around freely it would be extremely confusing and wouldn’t communicate anything. So we have to propose a path, make a narrative decision, but we don’t eliminate the freedom to navigate the space freely.

It’s interesting, and takes me back to the thinking around Marcel Duchamp’s origins in conceptual art and his desire to move away from painting. He wanted to remove the eye or hand from his decision making, and moved to drafting for a bit. You can see those drawings as phenomenally neutral and/or absolutely beautiful. They support a kind of rhetoric or aesthetics of objectivity, which I would say we try to bring into play as well. We can’t get away from the fact that we want to make beautiful things, but we need to make clear what the decision making process was that led us there, if that makes sense.

JA:

I would add that one of the strengths of the Maidan project is that there’s an archive of video associated with it. If you’re interested, or doubt the narrative, you’re welcome to go into that archive and see exactly what happened at that moment. There are pieces of evidence we are of course not going to show if our goal is proving that the police were in the wrong – but of course the defense will want to see what happened before and after the moments we chose to show, and they are welcome to do so.

I try not to use the word objectivity unless I am engaging a theoretical analysis of claims. Objectivity is a rhetorical claim that you use to convince someone you are telling the truth, when in reality, it is only your version of the story which you hope to convince others is ‘factual’. I think the strength of our work is that rather than scrubbing out everything we don’t think is right, we leave the option open for other stories to be told or for ours to be checked.

i•p:

Even in the design of tools and platforms there is bias and agenda. The increasing presence of cellphone footage, analytical algorithms, and IOT are dramatically shifting our relationships to space and to each other. How do you see these shifts playing out?

JA:

I’m totally frightened by what we can do. Just the technical capacity that Brad and I have access to gets better and better every year - and obviously can be used for good, or for ill. I think the default with most technologies is to benefit certain populations - usually those that created them - and have either negative or neutral effects on everyone else. It’s a tough question, but the answer I’ve always got from the Human Rights community is as long as we have access to the same capabilities we’re happy. It’s never been a satisfying answer for me, but it's the accepted one.

There’s been a lot of pushback in the academic space in particular, moving towards fair and accountable transparency. Understanding that the training data for AI technologies is biased is the beginning, but the real question is whether the critiques of these technologies actually make it into the spaces where these tools are developed or acting. There’s a long wait. The students getting trained now understand these issues more acutely, but won’t be in control of these technologies for another five to ten years. At least there’s a robust conversation happening now.

BS:

There’s a robust conversation happening where the consequences are acute. Say, in terms of criminal justice, human rights, or sentencing where you can say someone’s life is at stake. But there’s an insidious and dangerous parallel in issues that don’t feel as urgent, but end up shaping our built environment for the next decade. I went to a technology conference at Georgia Tech where all the titans of the construction industry were present, and the entire day was spent talking about how we can leverage algorithms, think about the future of mobility, and things like that to redesign cities from the ground up. There’s nothing wrong with that necessarily, but the people who were driving the conversation were all BIM experts and technologists who didn’t pose any critical reflection at all. It was crazy that there was no one there to critique this kind of capitalism of industry. The ethical questions weren’t even on the radar.

JA:

What’s the difference between a technocratic approach and what we have now? Without computers there were periods of architectural history where millions of churches looked the same, or even look at the houses in this neighbourhood, they could be in Austin or San Francisco or Boston, right?

BS:

I don’t think the difference will be in an aesthetic outcome. It’s a confidence in the internet of things and the cloud that monitors performance and organization for efficiency, as opposed to a more humanistic vision of how the city gets shaped and what is public space. There are so many questions that are fundamentally not algorithmic but are being put through this performative lens, and the answers are going to be super efficient but super terrifying.

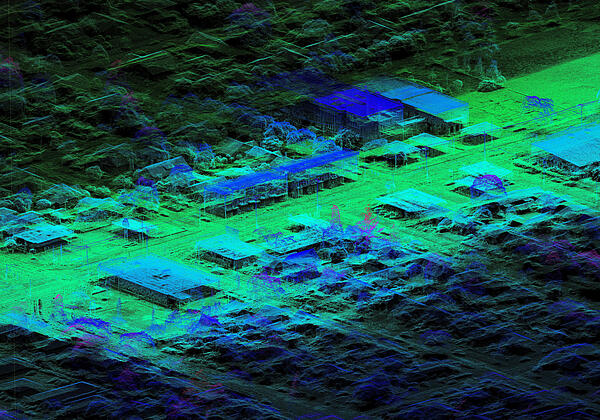

The other thing I find interesting from an architecture standpoint is how this changes our representations of space. Since the twenties the military has been able to fly over an area and give you topographic data, but within the past nine to twelve months we’re finally seeing computational powers deliver on the promise of photo-parametric-reconstructions. What’s super interesting about this is that it’s completely collapsing the distinctions between two dimensional representation and three dimensional space - the pixel is space. That’s a true paradigm shift. We can now move through color and XYZ coordinates in one model. Do we need sections anymore? Do we need plans? I think maybe not, or not consciously. This now allows you to move through the building, look through the body and it’s sections almost as vignettes. Rather than resolving three specific moments you can do it as a totality, and that’s crazy.

·