Stocktaking

Alex MaymindAlex Maymind talks to inter·punct about architectural pedagogy and education.

i·p:

How has architectural education adapted in the context of broad cultural changes such as the emergence of social networks, economic booms and busts, and digital technology’s increasingly pervasive role in everyday life?

Alex Maymind: The short answer is that schools have tried to do one of two things. 1/ Simulate the dirty realism of the world-at-large in the studio, often to speculate on how architecture can reflect larger cultural changes. Or, 2/ intensify the internal problems of the discipline, which are typically understood as problems of form and technique. In both cases, there is a palpable need to deal with the new or the contemporary—something that students typically crave, and rightfully so. In other words, what has changed and what has stayed the same has been a longstanding debate in architecture.

As alluded to in your own call for submissions for this issue, these paradigmatic cultural shifts have often been characterized within architecture as a crisis of sorts, often as a crisis of meaning, authorship, or architecture’s increasingly marginal relevance in society at large. Crisis fatigue and crisis mongering sets in rather quickly. According to a number of dominant postwar voices, architecture has been said to be in a near-constant state of crisis. This is perhaps less evident in professional schools of architecture than in disciplinary debates, but it’s still a pertinent situation to consider in light of recent crises. In general, architecture schools that pay close attention to the relationship between pedagogy and cultural changes are interested in teaching their students to engage the issues that are ten or fifteen years ahead, rather than simply cultivating design talent, or general acumen for the current milieu.

"This is a very important quote that is even longer than the last one, it'll really make you think. Like really really make you think."

To be fair, the long answer to the question depends greatly on the specific school in question. It is nearly impossible to address architectural education as a monolithic, homogeneous condition, considering that a wide range of alternatives and competing directions have emerged in the last twenty or thirty years. Some schools have resisted the idea that architecture must adapt at all, while others “ride the wave” in order to participate and reflect. If one were to draw up a quick history of architectural education, taking stock of the innovations in pedagogy would lead one to belief that architecture education is a constantly shape-shifting phenomenon.1 My own experiences as a student, juror, and teacher at a number of different schools have given me the chance to see the issue from a number of perspectives.

i·p: How does architectural pedagogy position itself relative to the world—or in more specific terms, how is pedagogy structured relative to the world? If, according to Isaiah Berlin, “the fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing,” then is it in the architecture school’s best interest to be a fox, or a hedgehog?2 With a few notable exceptions we often see evidence toward the former.

AM: The hedgehog versus fox analogy is incredibly apt to describe where pedagogical issues are today, despite seeming too dichotomous at first glance. My sense is that most schools—and here we must again grossly generalize—have become increasingly concerned with being fox-like, mostly because it has become both too difficult and too dangerous to pinpoint what the “one big thing” might be. Is it general architectural competence, or is it simply knowledge of the discipline? Is it architectural talent as demonstrated through a developed, comprehensive project, or the cultivation of an intellectual research thesis? None of these seem to truly hold as the dominant concern for an architecture school to aim towards. Historically speaking, the “big thing” since the 1950s has been the constellation of ideas, forms, and polemics known as ‘modern architecture,’ and its numerous variations and languages. Even if modern architecture came to be eventually understood as a kind of mirage, or what Tafuri called the “enigmatic fragments that are mute signals of language whose code has been lost…,”3 there was still a lingering sense that the code might somehow be recovered.

Perhaps a better way of reframing your question with Berlin in mind is: how can a school take on the productive attributes of both fox and hedgehog as opposed to being one or the other? Alternatively, you could argue that the ‘one big thing’ that architecture schools rely on is the centrality of the studio, where architectural problems and design question are engaged through making, drawing, modeling, conversation, and critique. I believe that there is still a certain sense of mystique around studio culture. We don’t quite know what happens when teachers leave for the evening and the students incubate and produce seemingly endless amounts of work. In other words, we don’t have an exact understanding of the model of creativity that is involved, and that is probably a good thing. On the other hand, we often take for granted the idea that the studio is an advanced educational system, perhaps because it is so ingrained in the culture of schools. Not long ago, the studio was a welcome disruption within the university setting. A 1970 issue of the RIBA Journal reflects this sentiment, “the design studio is probably the most rich and advanced system of teaching complex problem solving that exists in the university… Even as courses stand now, they have so much to offer students which cannot be obtained in any other university department.”4

In my own few years of teaching, I have tried to consistently connect specific architectural problems to what they mean in a larger cultural context. For example, we can start with the very basic proposition of displacement: when an architect decides to displace the front door from its traditional position, what are the consequences for the institutional identity or the site strategy? What does it mean to make a plan obsessively symmetrical in the tradition of something like Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin, and what effects does that have for the architectural promenade? These kinds of question lean on the idea that architecture has both a common sense relationship to the world that is established by seemingly obvious, self-evident norms, and an internal discourse that challenges and creates exceptions to those norms. For this kind of formulation to be valid, I would argue that there has to be some common basis for analysis and comparison, or a dominant paradigm that can sustain interrogation—in other words, a discipline of architecture. One of the facets of history that I have explored in my teaching is the way in which certain architects have attempted to stabilize a common ground for exactly this kind of analysis in order to produce a more systematic project as a result. The history of architects that advanced their theoretical ideas or projects through pedagogy is rich with examples of the connection between the codification of knowledge and an advanced, self-conscious interest in architecture’s history. One could think of Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, or Walter Gropius, or Colin Rowe in this regard. (More recently, architecture has been described as a family of special effects or a set of games).

In my seminars I have tried to highlight the way in which certain architects have constructed a sustained intellectual project in order to go beyond a superficial or momentary engagement with the contemporary moment. For example, in my “Delirious Koolhaas” seminar, the students spent a semester closely reading OMA projects through the lens of the modernist canon in order to understand the employment and bricolage of idiomatic tropes. Ultimately, the goal was not to simply unpack OMA (a feat in its own right) but rather to demonstrate the way in which Koolhaas has constructed a body of ideas by remixing a personal and unique subset of the modernist canon into novel combinations. One of the goals of the seminar was to demystify and deconstruct the legacy of Koolhaas by simultaneously considering his architecture with and without his writing.

Perhaps another important way of addressing the “hedgehog versus fox” question is to look at what happens in the very first, and the very last semesters of education. In other words, what do we teach freshmen when they arrive on campus, and what does thesis ask of students before they re-enter the professional world? As thresholds and bookends, the first and last semesters are two distinct moments when schools relay a very specific ideology about indoctrination and disciplinary, simply put: what is considered inside, and what’s considered to be outside.

i·p: In your Archipelagos studio at Cornell in 2012, you used two figures that saw history as both an operative device in design, as well as something fluid and malleable. In your teaching, history-as-operator seems to be an important method for structuring design. A recent conversation between Peter Eisenman and Pier Vittorio Aureli criticized architectural education in the United States as being obsessed with scholarship, and that this fact makes history-as-operation in design impossible.5

AM: As I am currently in the midst of a Ph.D. program at UCLA, this is a complex issue for me that I am still contemplating on a regular basis. I will say that most of the individuals that interest me have an intense or personal regard for history. Sometimes this is foregrounded, but more of than not, it is masked over. Having been trained as an architect, I tend to collapse the distinction between history and design into a smooth continuum—a continuum with some rocky bumps between the two far ends of the spectrum. The activities of designing and thinking about the past are not so distinctly separated in my mind. I think that certain architects tend to view history and design a highly compartmentalized manner, which is further reflected and reinforced by academic and faculty divisions, etc. That being said, I don’t think you can escape history. History is negotiated at every turn, and therefore it is not something you choose to engage or disengage. Every architect, and student, has a sense of the past even if only through an occasional history lecture or visit to the library to peruse the latest journal. To casually borrow from Nietzsche, we must not be slaves to history, but should use history to construct the present.6 I would say that any attempt to divide the terrain between designer, historian, and theorist is a suspect operation. Given that many designers also write, curate, and teach, the overlaps between these various roles are often much more interesting and productive than if they were more rigorously separated.

i·p: How do you attempt to mobilize history in the studio setting?

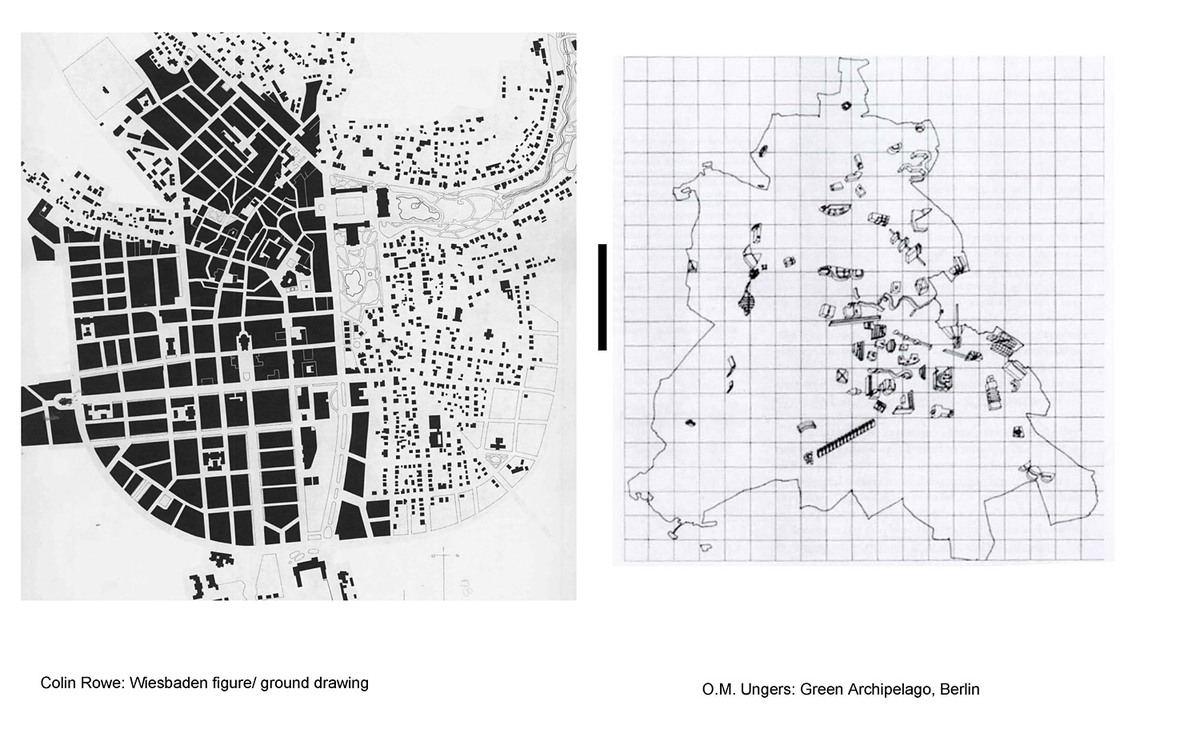

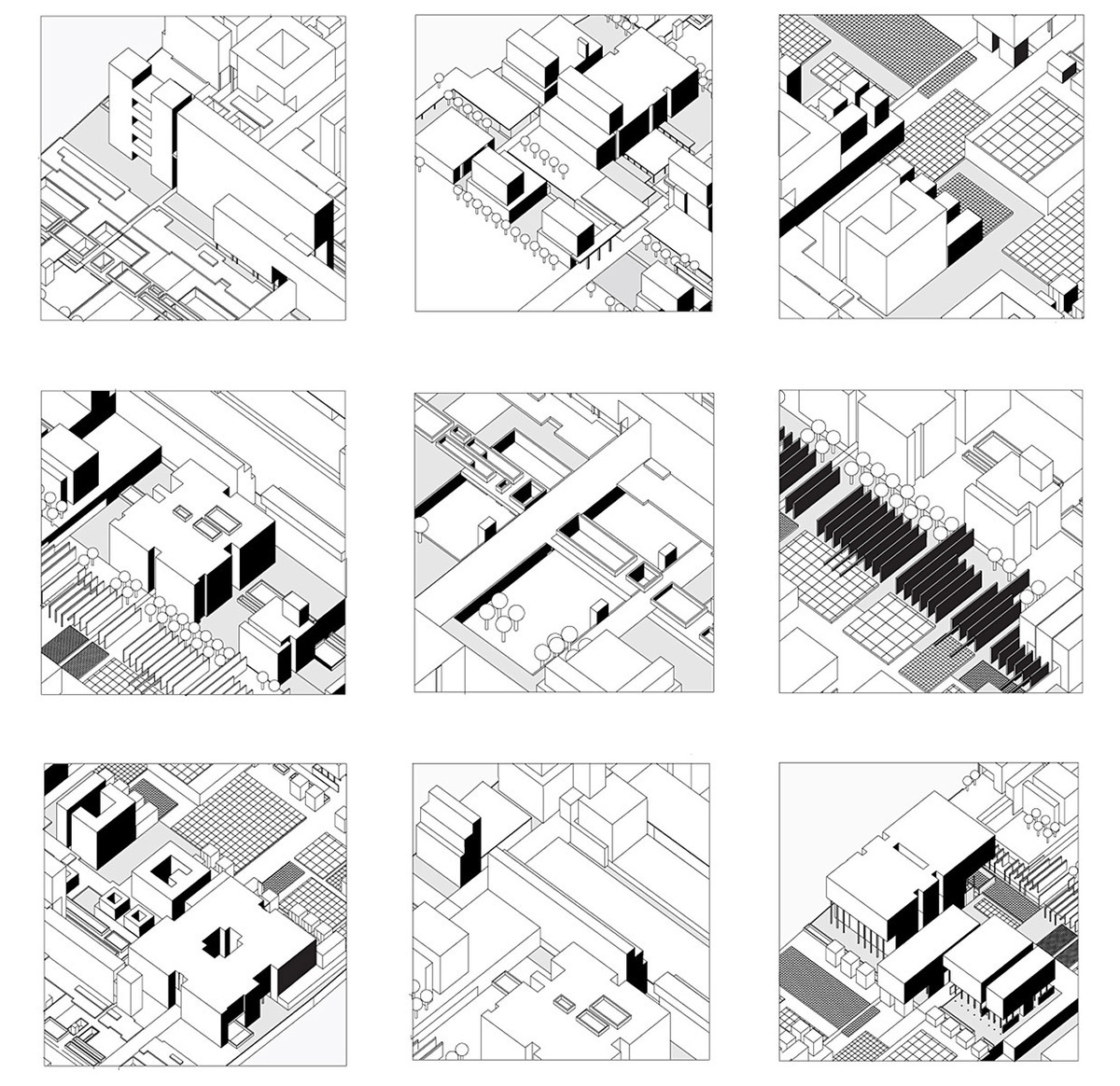

AM: I think that the Archipelagos studio mentioned above benefitted from directly taking on O.M. Ungers and Colin Rowe, not simply as formal precedents to copy and understand, but as disciplinary positions that have deep roots and specific ramifications that were pivotal to students’ design efforts. Also, because the students of Ungers and Rowe still teach at Cornell today, it was possible to understand the various positions that resulted from their respective projects and polemics. The main difficulty in the studio was to consistently foreground Ungers and Rowe during the semester while we developed the project itself; in that sense, our understanding of the past grew alongside the architectural design process. Since the project was an urban campus composed of multiple buildings that were meant simultaneously address an urban site and an architectural scale, the students had to contend with its public form, its collective dimension, and its relationship to New York City. The context of Roosevelt Island was as important as the historical questions, especially in light of the proximity and development of the island in the shadow of Manhattan, and its recent past as an incubator of competitions and manifestos. Roosevelt Island, as both an entirely separate landmass and a conceptual extension of the Manhattan grid, was dialectically positioned as simultaneously discontinuous and continuous with respect to its neighbor.

But, let me be clear—many design studios begin with precedent, research, or analysis. These are vague terms until further qualified and defined. The hard work, at least in this case, had to do with the amount of time spent making connections between the student projects at hand and a body of ideas that are larger and historically situated. Both Ungers and Rowe were intimately concerned with this issue; the idea of the city as a kind of laboratory. Ungers’ notion of the ‘city as a collection’ and Rowe’s ‘city as a museum’ both were acts of documentation—a polemical act in its own right, which bordered on hoarding—that were fundamental operations for engaging the contemporary city. (Rowe was a bit easier to untangle because the students were familiar with his early writings, and therefore, the kind of aesthetic pleasure and close reading associated with his genre of pictorial formalism.)

I would argue that the issue of precedents is the most dominant point of convergence in the work of the Ungers and Rowe, not simply in terms of repetition and imitation, but also as a conceptual problem that invokes a degree of self-consciousness about the intrinsic relationship between the zeitgeist and previous historical moments. Similar to the way in which the Five Architects placed themselves “in the secondary role, of Scamozzi to Palladio,” Ungers and Rowe engaged precedents not only as a methodological concern, but as an endlessly rich set of catalogued examples and fragments selected through a process of careful curation. For example, in the case of Rowe, he sought specific motifs in the history of architecture, such as the oscillation between figure and ground, unity amongst opposites, the tension between ideal geometries and contingent conditions, and local diversity within a totalizing order. Essentially, the issue of precedents is not simply a position of formal autonomy or a renunciation of a socially engaged architecture, but instead was understood as a desire to establish a transhistorical, though historically motivated, disciplinary position.

i·p: Do you structure a studio with a kind of hypothesis going in, or do you set up parameters and allow for intuition and individual exploration on the part of the students?

AM: The hypothesis was that the friction between Ungers and Rowe could provide traction for a contemporary urban design problem. The initial intent was to hybridize the two figures into a third position that might be able to learn from both. As the work progressed, and more analysis revealed the precise overlaps and disjunctions between the two, it became more useful to divide the studio into two groups that each would mobilize concepts from the legacies of either Ungers or Rowe. It’s critical to note that in addition to an in-depth study of the two architects, we also studied their pedagogical methods and even the student work from their studios in the 1970s. The other parameter was that each pair of students were to build one large physical model per week. Of course, this took quite a lot of effort, but I think it foregrounded a kind of close reading of form that is less likely in the use of two dimensional media—perspective drawings, renderings, or diagrams.

i·p: You recently edited Jeffrey Kipnis’ new book, A Question of Qualities: Essays in Architecture. Editing the work of a giant in theory—and also a renowned educator—must have been a daunting task. What are some of the challenges you faced?

AM:I studied with Jeff at Ohio State as an undergraduate, and since that time I have followed his writing closely. When I ran into him in New York City, I happened to have my binder of collected Kipnis essays, many of which have traveled with me over the years from place to place. The idea of publishing a book of his writings was a way of tidying up my binder and at the same time, making a greatest hits album of Kipnis essays that might be of some use to architecture teachers who have continually turned to his writings to articulate the finer points and nuances of a broad spectrum of ideas. He was generally amenable to the idea of the book, as was Log editor Cynthia Davidson, who also agreed that the book was long overdue. While choosing the exact pieces to include in the book took a bit of negotiation, it was generally a smooth process. Hopefully the final result stands as a meaningful record of Jeff’s impact on the field, and a useful companion to students or architects looking for a pseudo-spiritual advisor, or a shaman to illuminate certain dark corridors of architecture’s intellectual terrain.

1. For example, the ongoing research project Radical Pedagogies: Action-Reaction-Interaction, headed by Beatriz Colomina at Princeton University builds a history of architectural education in terms of its radical experiments. Joan Ockman’s recent book, Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America, takes an opposite tack, but similarly fails to present a total picture. Peggy Deamer’s review of Architecture School in the Fall 2012 edition of Constructs, highlights the enormous difficulty inherent to the task.

2. Isaiah Berlin, The Hedgehog and the Fox, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1953).

3. Manfredo Tafuri, “L’Architecture dans le Boudoir: the Language of Criticism and the Criticism of Language,” Oppositions 3 (1974), expanded in Manfredo Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labryinth: Avant-Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s, trans. Pellegrino d’Acierno and Robert Connolly (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987).

4. Royal Institute of British Architects Journal, January 1970, Vol. 77, London.

5. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Peter Eisenman, “A project is a lifelong thing; if you see it, you will only see it at the end,” Log 28: Stocktaking (Summer 2013): 71.

6. Friedrich Nietzsche, “ On the Use and Abuse of History for Life, Untimely Meditations, trans. Adrian Collins.