Site-Specific

Harry Gugger

Harry Gugger speaks with inter·punct about form, material, and the nature of corporate architecture.

i·p:

At Herzog & de Meuron, you worked on some of the most well known works of contemporary architecture, including the CaixaForum, the Tate Modern, its extension and the Beijing National Stadium, among many others. Perhaps similar to the contrast between, as you have put it, the American sensibility of architecture as a form of art and the Swiss sensibility of architecture with a much greater emphasis on building and construction, the work of Herzog & de Meuron is often architecturally extravagant and formal, while simultaneously retaining a much subtler, detail-oriented quality. As an example, the CaixaForum has a dramatic entrance promenade but is very quiet contextually, almost attempting to mimic its surroundings. How would respond to the idea that Herzog & de Meuron’s work plays formal extravagance off of the quiet detail?

Harry Gugger: I can say that when I was there, the extravagance, as you put it, was never an objective. If you want to drill it down to one priority, it was for the project to be specific. For us, being specific was about more than just responding to the site itself, but was also about addressing the needs of the client and the users. It was an obsession—our trademark—that we would try to profoundly understand who the people were that were going to be using our buildings in addition to what the client expected, what the site asked us to do, and also of course how the project could be built.

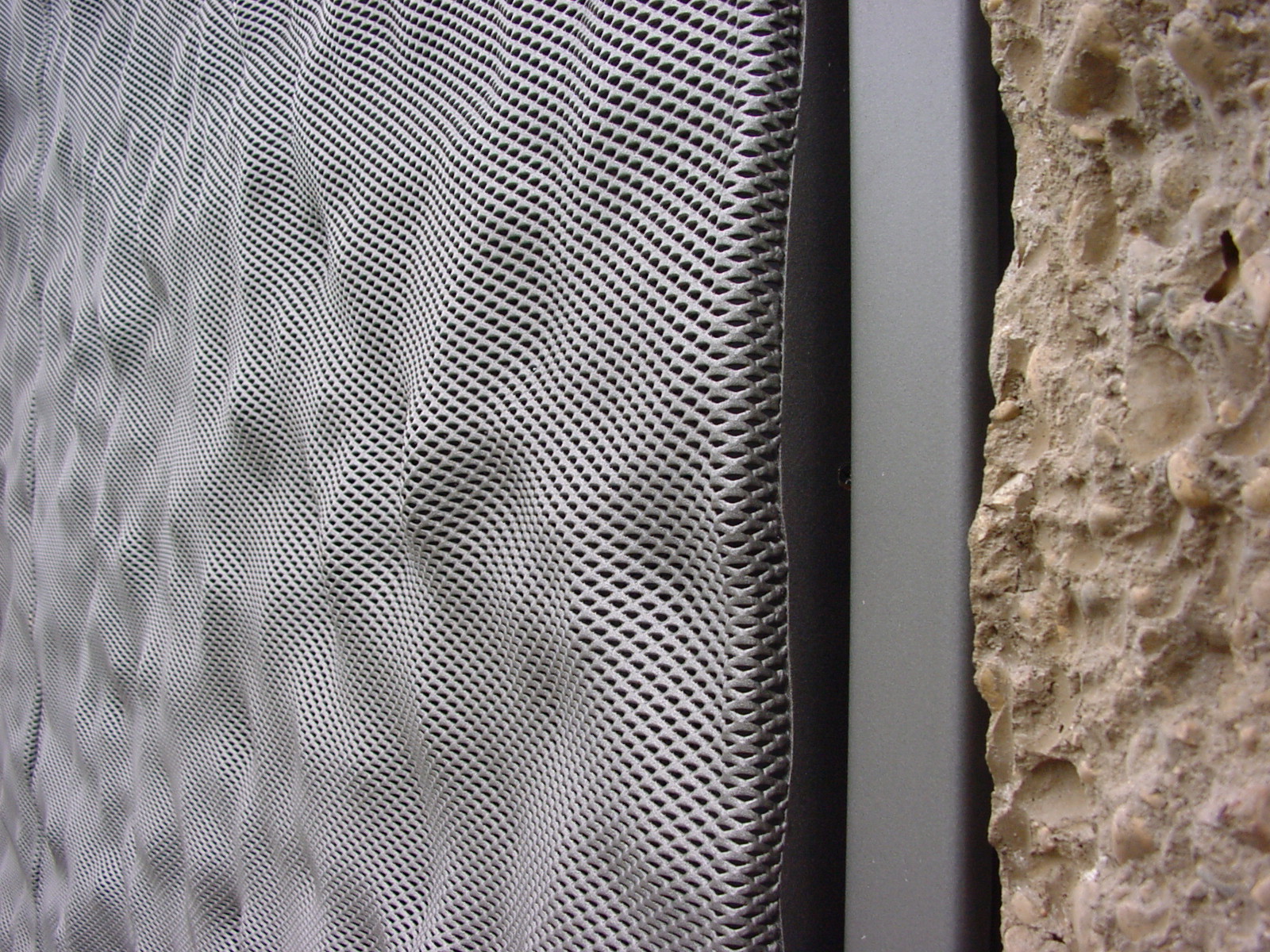

You mention the CaixaForum in Madrid. I would agree that it has an extravagant side to it, because why should a brick building float? But it was never the intention to float the building because we wanted to wow visitors. It was simply the result of an in-depth analysis of a complex site and program. When the client commissioned us to design the building, it was clear to us that as a museum, it also needed to function as a public space. The tight neighborhood however did not exhibit any notion of publicness—it was really quite residential. At the same time, just a block to the side, you had one of Madrid’s most beautiful boulevards, the Paseo del Prado, which the site was quite disconnected from. It was not certain at the time that the client would buy the petrol station which separated the site from the boulevard, so we were very focused on creating some form of public space. That’s where the idea to create a covered public plaza came from, and thus where the floating building originated—it was a necessity given the tight site. Yes, in the end, it looks extravagant, but it was part of the solution to fitting all the program the client was asking for in this historic, Heritage building that could not otherwise contain it all. Luckily, the petrol station did end up going, but back then that was not certain at all.

With regards to the detail, whether it is in the case of the Olympic Stadium in Beijing or the CaixaForum in Madrid, it would be easy to say that with such formal extravagance, the project doesn’t need much else, but this was never an option for us. We always also wanted to contribute towards how these forms would actually be built. Wherever the project was, we invested significantly in having our own people on site, always establishing our own office, be it in collaboration with a local architect or independently like with the Tate Modern in London. The contractors were not always happy to have us around, but for us it was important to pay attention to how things were being put together.

i·p:

With regards to your innovations in building materials and mechanical systems, for example with the consolidated mechanical systems you developed for the Schaulager and the very many material innovations, like the use of gabion walls in the Dominus Winery project, do you see building materials or mechanical services merely as a means to an end to solve a problem, or do you think they can create spatial opportunities in of themselves?

HG: I certainly see them as the ingredients with which you make architecture. To deny the role of building services would really be stupid—in fact, it would make their presence even more obvious. For example, if you decide not to include building services into your thinking from the beginning, you might decide upon a standard concrete slab and only then think about how to install the mechanical systems. This way of thinking makes building services all the more evident. It is a paradox: if you instead really consider them as being part of the architecture from the beginning and integrate them well, they actually then have less of a presence. In that sense, the Schaulager is an exemplary project, of which I have not been able to go beyond in my career. It was the culmination of the integration of building services, structure and the soil, with the excavated gravel defining the expression of the building. It was a very profound integration of what the site had to offer on the one hand and the program requirements on the other, which demanded a highly controlled environment for the storage of art.

i·p:

Similarly, were there times where a particular material or building technology became the launching point for a building? For you, at what point does material enter the design process?

HG: Let’s take the case of the gabions on the Dominus Winery. In their standard context as landscape elements, they are rather bothersome. But I would assume that every architect who is interested in materials and the built environment might for a moment think: couldn’t they also be used to make a building? From that moment on, once you have that thought, it doesn’t go away. Now, maybe not every architect is as insistent as we were and carries through with the idea when an opportunity arises to finally use the material a few years later, but this then is the creative act: perceiving your environment and constantly questioning that environment for its architectural qualities, whether it’s the built or natural environment.

When Christian Moueix commissioned the Dominus Winery, we knew that it was the moment to use the gabions in a building—so yes, there are these moments where you have an obsession with a certain material. The same is certainly true with the idea of silk printing on the Eberswalde Library—that was very much our theme for a long time. We first started silk printing on glass, but then progressed to concrete. Thinking of concrete as a material that can project an image, we developed the process of using a retarder to actually scratch the surface of the concrete so that images could appear in a manner that was true to the material.

i·p:

The Eberswalde Library is just one example of your many collaborations with artists to create inventive building features, not to mention other projects like the Laban Dance Center or the Ricola Mulhouse Warehouse. What do artists bring to architecture that architects do not? Why was it important for Herzog & de Meuron to incorporate artists as a part of the design process?

HG: In art, the question of perception is discussed on a level that is miles ahead of how it is discussed in architecture. From our point of view, there was always an enormous amount to learn from artists—just to name one, Rémy Zaugg. His whole career has been focused on interrogating questions surrounding perception: what part of art is our perception of the piece and what is actually the piece itself? What then makes an object a piece of art? How much of an artistic act is needed for something to be considered art? Additionally, in the beginning of his career Jacques Herzog actually hesitated between being an artist and an architect. He did sculpture in parallel to his work as an architect for quite some time, so he was very much attuned to art. As with the case of the gabions that I mentioned before, we were constantly seeking to integrate elements from outside the discipline, so why not integrate art?

i·p:

After working as a partner at Herzog & de Meuron for almost 20 years, you then started your own practice, Harry Gugger Studio, in 2010. How does your office differ in approach from that of Herzog & de Meuron?

HG: Well, it’s impossible to forget about what you’ve done and suddenly become someone else. Those 20 years at Herzog & de Meuron were fundamental. I strongly believe in what we did there, but Harry Gugger Studio is a very different office nevertheless for some very simple and obvious reasons. To start, it’s perhaps twenty five times smaller? Herzog & de Meuron is around 400 staff strong, and we are only 16. That makes for a very different office and was one of the reasons I moved—the machine was getting too big. For a very long time, up to 250 people, I knew the names of our collaborators, somehow managing to get to know them as they came and went. But one day during a coffee break, a young and enthusiastic trainee introduced himself and asked what my role was in the office. At that point, I asked myself if this was really where I wanted to be.

So size matters, and for this reason, we are very different. In addition, I like to believe that we are more modest than Herzog & de Meuron. I think that modesty and humbleness are important, and it’s difficult to remain modest and humble if you are pushed the way Herzog & de Meuron are pushed—you run the risk of getting a bit detached from the real world. Having said this, they still do a great job. Looking at their size, they come across as very un-corporate, but it’s of course much easier to be less corporate if you are such a small office like we are. So we are, I hope, less corporate, more humble and modest and that I believe is reflected in our work.

i·p:

Your firm has worked on projects at all scales, from interiors, to office towers to housing, to urban and even territorial design. What about an architect’s training makes them uniquely skilled to work at these varying scales?

HG: I have to say that I actually don’t think that architects are skilled to work at such varied scales. For too long now, the architectural object was too much of a focus in architecture schools. That’s why I felt it was necessary to cover both the large scale and the small scale when I started as a professor at the EPFL. It was a real battle though to try and offer a year-long studio and again and again, we were asked to adapt to a semesterly schedule. Our method however can only work when applied over the span of an entire year. With a semesterly schedule, students have a very fragmented and piecemeal understanding. If you decide to work on the urban scale on a semesterly basis, it’s not fulfilling, because it becomes too formal and very superficial. If you decide to work on the architectural scale semesterly, you’re missing the larger dimension and the constitution of the project's environment. Based on this thinking, we developed a pedagogical method at Laboratoire Bâle (laba) that flows from the urban or even territorial scale in the first semester, all the way down to architectural design and building detailing in the second semester.

i·p:

If as you said, architects are not well suited to working at such disparate scales, why did you insist to have laba teach to a full and wide range?

HG: That’s because urban design poses a lot of “wicked problems,” problems which don’t actually have a solution. Such problems can only be dealt with by an iterative process, each time improving upon your solution until you arrive at an optimal solution—not the solution, but an optimal one. Architects, trained in the design process, are very good at doing this. As a domain, we are skilled in bringing complex problems to the surface and presenting them in a digestible, easy manner. This is why it is important that architects don’t leave the larger scales to the urban planners, but that they get involved with these problems, exactly because of this capability. Dealing with city life and urbanity, there is not a single solution and you have to be aware of that, knowing that if you favor one option, you disfavor another, consequences which have to constantly be balanced. It’s important not to cut off the complexity, but allow it to be part of your solution.

i·p:

At laba, your research specializes in investigating the relationship between architecture and nature and the dichotomy between the urban and landscape. What led to this focus on such perhaps disparate topics?

HG: The sheer fact that I don’t think these topics are disparate. Back when the city first appeared, the dichotomy between the city and the countryside was a productive one—these terms spoke of a divide that actually structured space. But following the model suggested by Cedric Price’s “City as an Egg,” the city/countryside dichotomy has dissolved. Therefore, it’s very important to discuss these issues by saying that this dichotomy has become a metonym. There are no more strict boundaries: there is one Earth, an industrialized and urbanized Earth. To think that wilderness still exists today is wrong and unproductive.

i·p:

Like you touched upon, architectural education has come under criticism recently for being out of touch with the realities of built practice, with too much of an overt emphasis on formality and speculation. Some might even argue that speculative research is self fulfilling and irrelevant to the actualities of day-to-day practice and the profession. What value do you see in speculative research and how can it be reconciled with the demands of industry?

HG: Well, would you like to surrender to the demands of the building industry? The industry is actually in complete denial of our profession. Having said this, why should we not take the freedom to engage in speculative work? If you decide not to and maintain a very narrow idea of what architecture is, you completely deny the power of architecture. And as I said before, the building industry doesn’t need us anymore. Yes, of course—many of our colleagues end up employed by this industry—but I don’t believe they are the architects who really believe in the power of architecture.

Now, this might all sound very negative, but if you take the example of the film industry, there is a coexistence between Hollywood with its blockbusters, and alternative or independent cinema that will never go away. You can find many references and techniques in blockbusters that somehow originated in independent cinema. Because it addresses a small audience, independent cinema has the liberty to be more radical, avant-garde, and trend-setting even. Its role in the industry is to remain highly speculative and autonomous.

CB: To conclude, Swiss architecture is traditionally well known for its strong craftsmanship, materiality and attention to detail, but with the consequence that perhaps it doesn’t often address the larger scale, or these “wicked” problems. With the work of your practice and teaching as an example, is that changing? Where do you see Swiss architecture going?

i·p:

What I would ultimately hope for is that Swiss architecture retains its care for the built—that this does not disappear. It’s a quality that, having built abroad, does seem to be something really quite special. I dare to draw a line between Dutch architecture and Swiss architecture for this reason. Having said this, this is not only in the court of the architects. I insist that the culture of construction and craftsmanship contribute just as much to the quality of architecture. It is important that the architect, even when working globally, continues to advocate for the attention to detail and care for construction. Otherwise, we risk falling into the trap of diagrammatic architecture and shy away from architecture that understands itself in a more complete way.

I would also hope however that we understand that our concern is not limited to the single structure, but consists instead of the whole built environment. Architects should be keen to design not just the single new building, but should be really ready to address the entirety of the built environment as an architectural project. This we try hard to imbue our students with—to address problems outside of our domain. When I look around at the latest generation of Swiss architects, I see this concern in them.